The Importance of Photography in Abolition

By: Iliyah Coles

Photography’s Greatest Role

Photography has played a major role in the abolition movement, both then and now. Photographers within the movement have used and continue to use the medium to document various peoples in life’s tragedies and successes. Frederick Douglass spoke about the art of photography in numerous speeches and essays. In this essay, I will discuss a couple of those speeches and relate them to photography in both the Civil Rights Era and the current Black Lives Matter movement. The goal of this piece is to express that photography’s greatest role perhaps is to humanize the lives systemic racism often desensitizes.

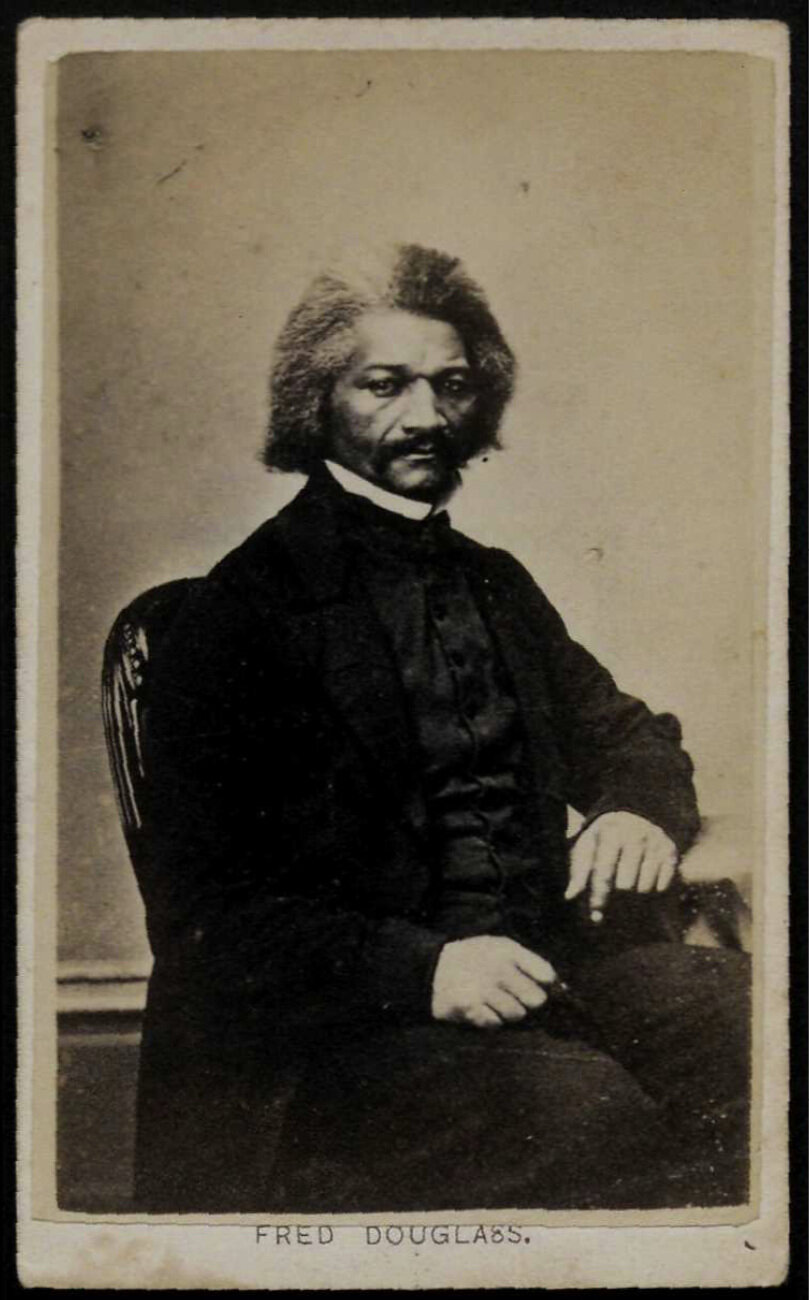

A front-facing photograph of Douglass. (c. 1855)

A picture of Frederick Douglass’s signature.

Frederick Douglass, a formerly enslaved person, was the most photographed American of the nineteenth century. (c. 1870)

Douglass’s Speeches/Writings on Pictures

Douglass had numerous writings on the role of photography. His “Lecture on Pictures,” given on December 3, 1861 in Boston’s Tremont Temple, explains photography’s importance in signaling progress (Stauffer, Trodd, & Bernier, 2015, pg. 126). Throughout the essay, Douglass expresses his fascination with the picture and all of its abilities. He states:

As an instrument of wit, of biting satire, the picture is admitted to be unrivalled. It strikes human nature on the weakest of all its many weak sides, and upon the instant, makes the hit palpable to all beholders. The dullest vision can see and comprehend at a glance the full effect of a point which may have taken the wit and skill of the artist many hours and days. (Staffer et. al., pg. 129)

The practical side of pictures is exemplified here; they are often a quick way to capture a specific moment. Douglass further argues that “the whole soul of man is a sort of picture gallery” (Stauffer et. al., pg. 131). Our lives consist of moments—glimpses of the events and people that have shaped us. Pictures are always more than just pictures. With each one, we associate something else, and something seemingly objective instantly becomes personal.

In “Lecture in Pictures,” Douglass also connects picture making to the war; he saw pictures in relation to progress. He states, “Great nature herself, whether viewed in connection or apart from man, is in its manifold operations a picture of progress and a constant rebuke to [the] moral stagnation of conservatism” (Staffer et. al., pg. 140).

“Rightly viewed, the whole soul of man is a sort of picture gallery, a grand panorama, in which all the great facts of the universe, in tracing things of time and things of eternity, are painted.”

-Frederick Douglass, Lecture on Pictures

“Art is a special revelation of the higher powers of the human soul. There is in the contemplation of it an unconscious comparison constantly going on in the mind, of the pure forms of beauty and excellence, which are without to those which are within, and native to the human heart."

-Frederick Douglass, Pictures and Progress

Photograph of Frederick Douglass taken in 1880.

Source: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/6e4b45d3-4aae-6652-e040-e00a1806645c. Douglass’s “Pictures and Progress” more closely details the relation between photography and revolution. “Pictures and Progress” was written between 1864 and 1865, and it was based on references from a speech he gave (Staffer et. al, pg. 161). Douglass was supposed to be making a speech about pictures but could not achieve this goal without discussing the impact they have made on society. Perhaps one of the most fitting quotes to the interest of this essay reads: “[…] for a man’s picture, however homely, will, like himself, find somebody to admire it. No man contemplates his face in a glass without seeing something to admire” (Staffer et. al., pg. 165). This quote explains the photograph’s ability to humanize its subject(s). Someone has to find something to admire about the picture; it is simply a human tendency.

Douglass states, “Art is a special revelation of the higher powers of the human soul” (Staffer et. al., pg. 169). Looking at pictures—experiencing pictures—becomes a revelation. It takes us out of our minds, even if just for a second, and allows us to simply feel. This experience links us despite all of the factors in life that do the opposite. Douglass consistently states throughout the essay that no other creature except humankind has the ability to make and appreciate pictures (Staffer et. al., pg. 170). This is why, when we experience them, we are able to find something in which to relate and connect.

Douglass further explains:

It is the picture of life contrasted with the fact of life, the ideal contrasted with the real, which makes criticism possible. Where there is no criticism there is no progress, for the want of progress is not felt where such want is not made visible by criticism. It is by looking upon this picture and upon that which enables us to point out the defects of the one and the perfections of the other. (Staffer et. al., pg. 170).

This is such an intriguing quote because it connects pictures and reform so vividly. This battle between real and ideal is present in pictures and many other aspects of life, even life itself. This struggle and constant critique of the world is the first step to improvement. Douglass’s claim directly correlates with a speech he gave in 1847, called “The Right to Criticize American Institutions,” which details criticism as a fundamental American ideal (https://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/the-right-to-criticize-american-institutions/). Abolition, which I will discuss later, is itself a criticism of existing institutions.

One of the most interesting things I found about Douglass’s “Pictures and Progress” is that Douglass is not necessarily coming from this grand critical viewpoint. He is not studying photographs through the lens of artistic technique. He is simply observing and documenting these observations. His credibility is being a human himself and understanding what it feels like to look at a picture.

Using Douglass’s Work as a Lens

Douglass’s views on photography can be used as a lens through which to view the many photographs taken during the Civil Rights Era. In Deborah Willis’s description of photographer, Carrie Mae Weems’s exhibition, she states, “Photographers and artists like Carrie Mae Weems have contributed to our politicized cultural climate with acts of visual self-representation and new expressions of black pride and identity” (Weems, 14). Carrie Mae Weems began constructing this exhibition called Constructing History: A Requiem to Mark the Moment in 2007 with the goal of reflecting on historical moments that have shaped Black life (Weems, 28). Like Weems, many Black photographers used the medium to document reform and progress.

Pictures have an effect on every person who witnesses them. This is the reason many widely known photographs from the Civil Rights Era (such as the ones displayed further below) became as popular as they did. Many of these photos humanized Black people in a way that had never been done before. They captured horrific, unnecessarily hateful events bestowed upon an already oppressed group of people. And instantly, even if just for a second, whomever glanced at a photo like this felt something for its subjects. They looked at these pictures and found some way to relate—some way to remind themselves of our shared humanity.

To the far left is abolitionist, Harriet Tubman, pictured with former enslaved persons she helped escort to freedom. (c. 1885)

We are able to see photography function in this way time and time again. It started in the first abolition era, with Frederick Douglass, a former enslaved person, becoming the most photographed American of the nineteenth century. Chattel enslavement was not abolished in America, officially, until the passing of the 13th amendment in 1865 (https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=40). Douglass became a widely publicized figure long before then, giving speeches and writing pieces in support of abolition. His picture was widely spread as well—humanizing an individual formerly enslaved, an individual formerly considered property. It is highly probable that photographs and portraits of Douglass helped to rework the narrative of the Black man in a way that may have convinced Americans to rethink the meaning of enslavement.

Ruby Bridges, then six years old, had to be escorted to and from school by U.S. Marshals just to be able to learn with White students. (1960)

We see photography function in this way even in today’s era especially now with the Black Lives Matter movement and the call for the abolition of the police. The footage of George Floyd’s lynching by police officer, Derek Chauvin made his story unavoidable, specifically to White audiences. There was no longer room for fabrication. The evidence existed and the picture was clear: A White man’s knee was on a Black man’s neck. And it was there for over nine minutes.

The photo of Ieshia Evans protesting in Baton Rouge was taken in 2016. The protest was in response to the excessive force the Baton Rouge Police had been known to use against Black people following the killing of Alton Sterling (“A Single Photo from Baton Rouge That’s Hard to Forget,” 2016). In the photo, there are two police officers dressed in full armor to detain Evans, who stands tall, head high, with her arms in front of her—unmoved. This photo is one that I think resonated with a lot of people, including myself. As a Black woman, I see some of myself in Ieshia Evans. I look at this picture and feel a lot of things, but the most prominent feeling is empowerment. She stands there in the midst of unnecessary force ready for whatever comes next.

I think photos like these help combat the one-dimensional narrative that is often created about Black people. Photos like these humanize Blacks—making us visible in all of our extraordinary and ordinariness. Douglass related pictures to progress in the way that we cannot look at a photo and not find something to admire. Systemic racism fights to take that ability away. It fights to make Black people invisible and meaningless and undesirable, which is why photography is itself a form of activism and a means for abolition.

Works Cited

Appelbaum, Yoni. “A Single Photo from Baton Rouge That’s Hard to Forget.” The Atlantic. 10 Jul. 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/notes/2016/07/a-single-photo-that-captures-race-a nd-policing-in-america/490664/. Accessed 6 Dec. 2020.

Staffer, J., Trodd, Z. & Celeste-Marie Bernier. Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2015.

Weems, Carrie Mae. Constructing History: a Requiem to Mark the Moment. Savannah, Ga.: Savannah College of Art and Design, 2008.

The Birmingham Fire Department uses powerful hoses, specifically designed to fight fires, to spray human beings exercising their right to protest. (1963)

Following a protest for the killing of Michael Brown, a woman kneels on the concrete with her arms outstretched, surrounded by fire and tear gas. (2014)

Ieshia Evans stands boldly still as two officers rush to detain her following a protest for the killing of Alton Sterling. (2016)